A Gold heist in Australia 1878?

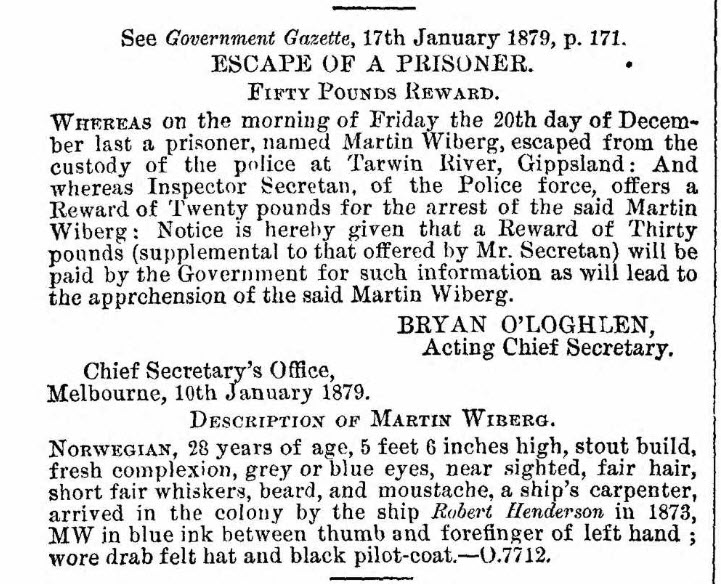

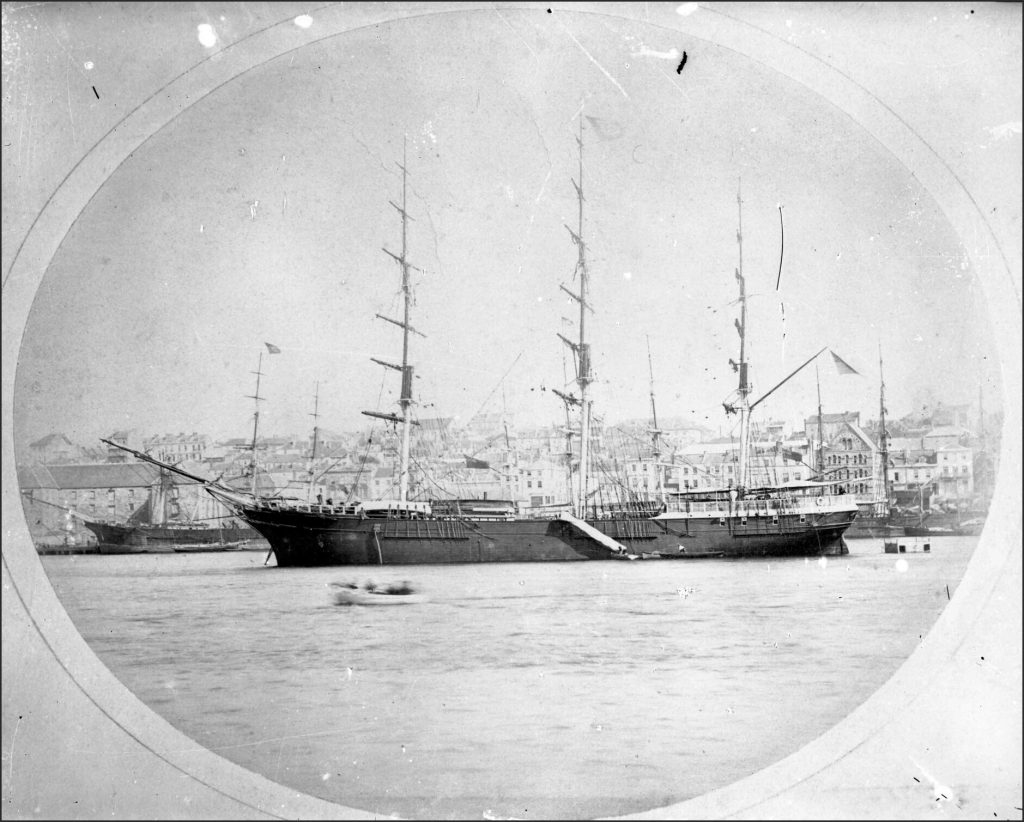

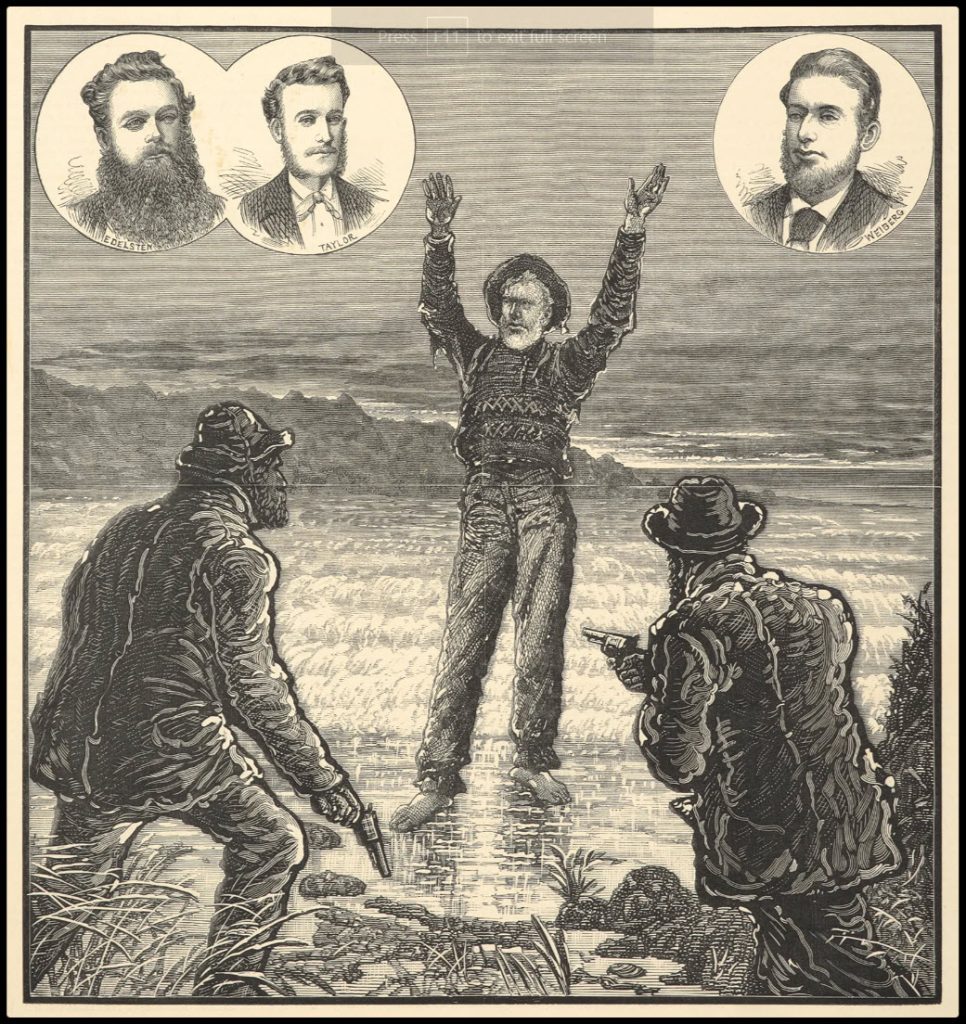

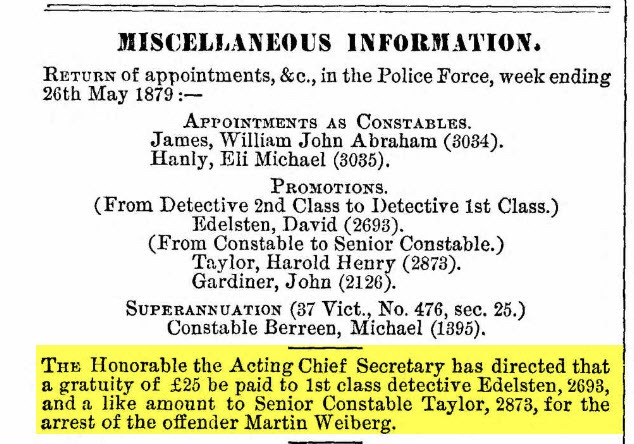

The Avoca Gold Robbery: It seems there is a criminal in the Sundheim ancestry, that could not resist the temptation of committing a serious crime in 1878. As the information from police reports and court minutes might suggest, there are several other persons involved in the theft. According to an article in the australian “Victoria Police Gazette” on 22 jan 1879, a norwegian ships carpenter, Martin Wiberg (aka Viberg, aka Wieberg) escaped from prison on the 20 Dec 1878. A £50,- reward was offered for his capture, which was a quite high reward at the time. This was to be known as the “Wiberg Robbery”, and became one of the most famous robberies in Australian history. To this day people are searching for the remaining gold sovereign coins, since less than 1/4 of the stolen sovereigns was recovered. Other question we seek to answer in this article are: Could there be any living decendents after the brothers Martin & Mathias “Matthew” Olsen Viberg, and the half-brother Fritjof Jacobsen? , and what happened to the brothers father, baker Mons Olsen Viberg?

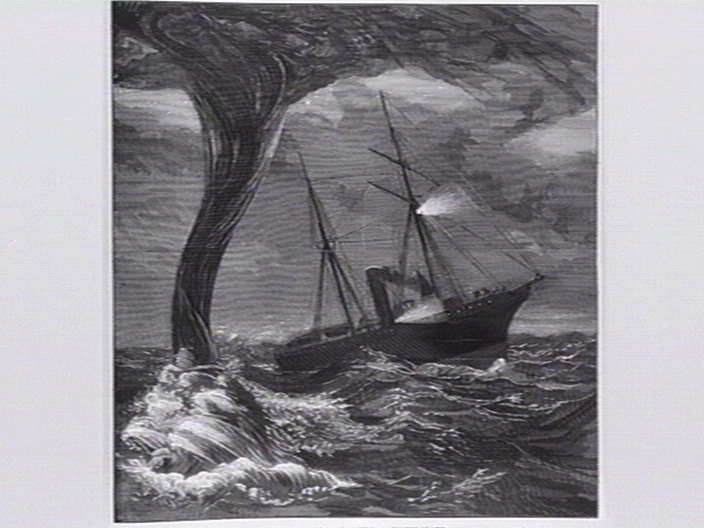

Martin was arrested for allegedly to have stolen 5000 Gold Sovereigns of the Royal Mail Steamer “R.M.S Avoca” on her journey from Sydney to Melbourne. The theft was clevery masterminded and executed, and the missing Gold Sovereigns was not notised until many weeks and months after it had occured. Martin escaped from capture, but was arrested again near Cape Patterson and centenced to 5 years in the HM Pentridge Prison for “The Weiberg Robbery”. Only about 1500 Gold Sovereigns has been recovered, which could suggest that other people after all had some part in this robbery, and/or that some 3500 “bullions” gold Sovereigns are still hidden in some secret hidingplace at Inverloch near Melbourne, Victoria.

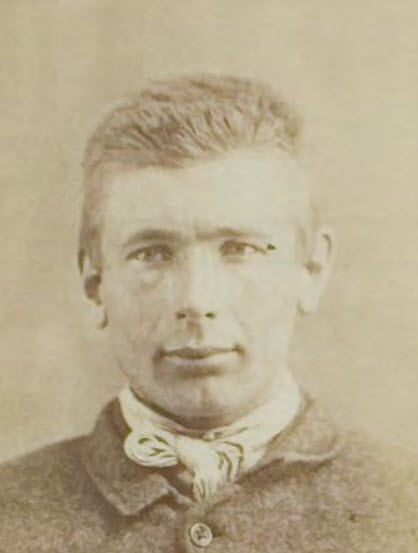

(Cover photo, Martin Wiberg from Australian prisoner records 1880)

Martin Wiberg, 28 year old. According to the Police Gazette, he came to the colonies with the ship “Robert Henderson” in 1873. According to another record on Ancestry, Martin Wiberg, ablebodied seaman, age 21, arrived from London to Sydney with the ship “John Duthie” in August 1872. According to other records on Ancestry.com, Martin was married to Rosina Brackley in 1875. As records shows, Rosina was also employed onboard the P&O Co “Ellora” and the “Avoca”, and we can assume they first met onboard one of these ships.

Martin Wiberg was born in Åsgårdstrand, Norway in 1851. He was son of baker Mons Olsen Viberg b.1822 og Maren Evensdatter b.1827. He was Great Grandson to Erik Andersen Sundem b.1774. Martin became an ablebodied seaman and went to sea about 1868, and his brother Mathias followed suit in 1872. According to his norwegian seamans’s records, he “escaped” a vessel in 1871, and that was the last on record in Norway.

In the norwegian national census for Åsgårdstrand in 1875, it is noted that Martin Wiberg is in Australia, which makes it very likely this is the same person as the robber. In addition, the census shows Martins half-brother Frithiof Jacobsen b.1859 (aka Frithjof Edvard Jacobsen or Fred Jacobsen), listed as a seaman and also currently in Australia. This fits with information that there was a 3rd brother mentioned in some of the newspaper stories. The two brother probably came to the colonies about the time when Martin was realeased from prison in 1883. The brother Matthew sailed the yacht “Neva” after this was purchased. He was questioned onboard by police, since they were still searching for the remainder of the gold sovereigns. The brothers were all sailors of the lowest ranks, and would never be able to afford such a vessel, so ofcourse they must have had access to some of the gold to purchase and operate this yacht.

Martin was living i Wellington Park, Williamstown, Victoria, Australia in 1877

What was the fate of the Vibergs in Australia?

Others have been wondering. Found this very interesting website at martinwiberg.net

According to the website, Martin Wieberg was released from prison in 1883. Afterwards he made his way to Hobart where he joined his brother Matthew Olsen onboard his newly purchased yacht “Neva“, they sailed back to Warratah Bay. After some strange circumstances while trying to escape police yet again, Martin alledgedly drowned during an attempt to get across to an island where his yacht was waiting. Then escapeplan included to bring his wife and daughters to his yacht “Neva” and go to New Zeeland. In the process, his wife & daughters refused to go with him. After this event, his body was never recovered, and many rumors was formed that he had joined some sailing vessel and escaped to Europe. Martin and Rosina had two children: Ethel Christina Wiberg, and Lena Martina Wiberg. Martin’s wife Rosina Brackley remarried Master Mariner John Leith in 1884, and the children survived. Captain John Leith was mentioned in several reports to be master onboard the schooner Gazelle which sailed the waters of Warratah Bay, and he was also a vitness in the court proceedings. Ethel married Peter Pescia in 1902, and Lena married John Middleton Siggins in 1910.

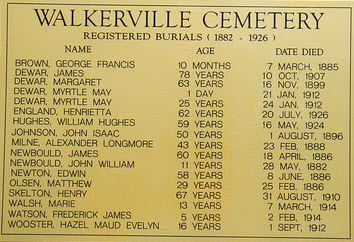

The brother Matthew Olsen, aka Mathias Olsen Viberg, married Margaret McDonald on the 3rd January 1888 and they lived at Waratah Bay. They had 2 children, Martin and Mathilda. According to news reports, Matthew died by accident while fishing at Warrath Bay in 1886. The son Martin passed away in 1901, while Mathilda survived and married Joseph Wilding in 1914. Joseph & Mathilda had 4 children. Matthew Olson is buried at the Waratah Bay historic cemetary.

The half-brother Frithiof Edvard Jacobsen (aka Fred Jacobsen), possibly the 2nd person mentioned to be onboard the “Neva”, but has not been found in any records since. The name seems to not be mentionsed in any available records, which in it self is very mysterious, as both the other brothers appear in available crewlists and immigration records. There is a possible match to a “Fred Jacobsen” in Alaska USA, and there is no confirmation that Fred ever returned to Norway. Any hints regarding Frithiof Jacobsen would be much appreciated, so please get in touch! Could it be that also he settled in Australia at the time?

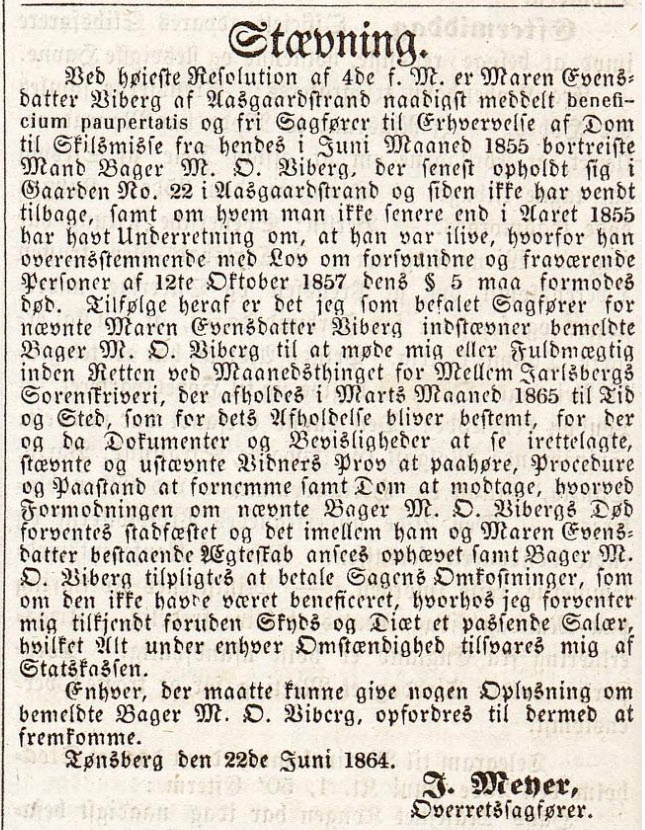

What really happened to the father, Mons Olsen Viberg?

An important question is: what really happened to their father, Mons Olsen Viberg? It is very likely that this story started with a dramatic event long before the sons sailed out into the world. The father dissapeared sometime between the birth of Mathias in 1855 and the national census in 1865. The father is not listed in the census, but in the census notes is is written: “The husband, Baker M.Viberg is abroad”. Later, in the national census for 1875, the wife is listed as Widow, and the mother and a daughter is now supported by the Communal Poverty Services. In May 1855 it seems that baker Viberg is bankrupt, and travels abroud shortly after. In 1864 the wife Maren Evensdatter is seeking the courts for a divorse, since the husband have been dissappered since he left home in June 1855.

Martin & Matthew had a sister, Olufine Mathilde b.1853, back in Norway. They also had a half-brother, Frithjof Edvard Jacobsen b.1859 (aka, Fred or Fritjow I. Cederberg) , who also became a sailor. The mother and the daughter is found in the censuses 1900 & 1910, and they are living in a poverty shelter, just barely managing. The mother Maren passed away in 1914, and Oluffine passed away in 1920, still unmaried. This poverty started basically when the sons went to sea, and may very well be some of the reason/motivation for the desparate deed of the theft, who knows?

Message to all conspiracy seekers

The narrator of this website have researched the ancestry of the Vibergs, and nothing indicates that Martin ever returned to Norway, or Sweden, that some source seems to have indicated. Martin worked on various norwegian merchant vessels until he ran away from his last vessel in Swansea, UK in Sep 1871, and then he is not seen in Norway again. A Martin Wiberg, AB, age 21 is crew on the “John Duthie, arriving from London to Sydney in Aug 1872. He works as a carpenter on the RMS Avoca for a few years and became the famous “Gold Robber of the Avoca”. His younger brother Mathias (Matthew) Olsen was also a sailor on norwegian vessels. He seemed to have a longer career on norwegian vessels from 1871 until 1882. It seems he may have signed off a vessel in Australia on 4th July 1882, probably trying to reunite with his older brother Martin upon his release from prison.

What is maybe puzzeling is how Mathias supposedly suddely owned a ship, the small cutter Neva, at such a young age, when his brother was realeased from prison. They came from a very poor upbringing, as they lost their father while in their teens. The mother and their sister was living at the national census of 1910, still supported by the communal poverty services. A theory is that the stolen gold very possible was a desparate attempt to grab a unique opportunity as the carpenter onboard the Avoca, and possibly bring this fortune back to Norway and “rescue” their mother and sister from really unfortunate circumstances. On the other hand, Martin got married in 1875 in Australia, and had two daughters. His own new family may of course also be the main motivation. There are of course no excuses for such acts, but that is probably closer to the truth than anything else. Obviously the ship “Neva” that the brother seem to have, was probably obtained from the possession of the gold, or possibly other bad deeds, because the brothers were not well paid marine officers, just merely young ablebodied seamen. Records also showed that Matthiew first arrived in Australia in 1881. It was mentioned that Martin had two brothers onbard a ship at the time of his release from jail. The facts may support this claim, since the norwegian census for 1875 is stating that both brothers Frithiof and Matthew are in Australia. The younger half-brother Frithiof was working on norwegian vessels until abt 1894 according to norwegian seamans records. However, the final destiny of the half-brother Frithiof is yet to be determined. There is no proof to support that Martin survived the famous swim across the “Andersons Inlet” of Inverloch in Victoria, because there is (so far) no evidence to support such a claim. That should be good news for those still searching for the remaining gold sovereigns in the area of Inverloch. Another funfact is how the amount of gold sovereigns grev from the original 5000 to 15000 coins in the newspaper reports, and possibly the most interesting is that the gold sovereigns were a unique minted version from 1877, and still to this day there are abt. 3500 coins not accounted for.

If you are in any way related to Martin & Matthew Olsen Wiberg and their decendents, kindly get in touch via the contact form please.

THE BULLION ROOM – THE STORY HOW THE THEFT WAS MASTERMINDED

Martin was employed as the Avoca’s carpenter. As the ships carpenter, he had been asked to repair the lock on the bullion room door, and when doing so, he took an imprint of the key in wax.

He then had access to the Bullion Room where he crafted a secret hatch that allowed him to enter the room without being seen by navigating the hidden tunnels of the ship.

The trip from Sydney to Melbourne encountered stormy weather which provided the perfect cover to muffle any sounds that he might make in extracting the sovereigns. When everyone was asleep he entered the bullion room and with a cold-chisel carefully pried open a box marked “X.O.X”. Inside the box was sawdust, and underneath a smaller box with seals. Martin took a hot knife and melted the wax on the seals before removing the sovereigns. He then restored the boxes to near original condition so that his deed would not be detected until long after he had left the ship at Williamstown.

(Text and copyrights from martinwiberg.net website)

Other Relevant links

- John Duthie

- Robert Henderson

- Robert Henderson 2

- Census 1875

- R.M.S Avoca

- R.M.S Avoca in Alfred Graving Dock after 1885

- Central Register for Male Prisoners p.29

- Waratha Old Cemetary

- Waratha Old Cemetary 2

- “John Duthie” arrival 29 Aug 1872

- Crewlist “John Duthie” 1872 – Martin Woberg, Norwegian 21 yrs.

- Crewlist “John Duthie” 1872 – Scanned

- “Robert Henderson” expected from London 12 Dec 1873 (sailed from London 9 July 1873)

- Avoca PAX record 18 Mar 1876

- Avoca PAX record 10 Jun 1876

- Gold Sovereign 1877 value?

- ABC News Australia

- Odd Australian History website

- Illustrated Australian News 3 Oct 1877

- The Argus 31 Oct 1878

- Kerang Times 1 Nov 1878

- Nelson Evening Mail 19 Nov 1878

- South Bourke and Mornington Journal 21 May 1879

- Illustrated Australian News 7 Jun 1879

- New Zealand Herald 26 Jul 1879

- Portland Guardian 4 Dec 1883

- Bendigo Advertiser 16 Oct 1883

- The Launcheston Examiner 20 Oct 1883 – Interview with Capt John Leith

- Mount Alexander Mail 5 Jan 1884

- The Age 18 Mar 1886

- Wreck of The Cutter Petrel 16 May 1888

- The Oakly Leader 16 Dec 1893 – Skeleton found

- Oamaru Mail 9 Feb 1897

- The Advertiser 28 Jan 1897 – The “Tararua Gold Robbery” in Nov 1880 ????

- Kilmore Free Press 25 Nov 1880 – Extensive Gold Robbery from the S.S Tararua

- The Maffra Spectator 1 Dec 1904

- Otalgo Daily Times 17 Aug 1906

- The Will of John Leith 21 Jul 1908

- Evening Star 3 Jan 1930

- The Argos 8 Jan 1938

- The Argos 22 Jan 1938

- The Great Southern Star 23 Jan 2018

- Victoria Police Museum

- HM Pentridge Prison

- The Inverlock Treasure

- WesternDistrictFamilies.com (The Argus 22 Jan 1938)

Vessel arrivals – Immigration records for Martin

- “John Duthie”, arrival Sydney from Melborne 30.08.1872 (this seems to be the actual first arrival of Martin Viberg to Australia, and not with the vessel “Robert Henderson” in 1873 as described in the “Victoria Police Gazette” in 1879)

- (“Robert Henderson”, barque, arrival 11 dec 1873 from Sundsval 12 aug.)

- “Ellora”, arrival Sydney from Melborne 01.06.1875

- “Ellora”, arrival Sydney from Melborne 26.07.1875

- “Ellora”, arrival Sydney from Melborne 25.08.1875

- “Ellora”, arrival Sydney from Melborne 21.09.1875

- “Ellora”, arrival Sydney from Melborne 19.10.1875

- “Ellora”, arrival Sydney from Melborne 16.11.1875

- “Ellora”, arrival Sydney from Melborne 20.12.1875

- “Ellora”, arrival Sydney from Melborne 14.01.1876

- “Ellora”, arrival Sydney from Melborne 18.02.1876

- “Avoca”, arrival Sydney from Melborne 28.06.1876

- “Avoca”, arrival Sydney from Melborne 06.07.1876

- “Avoca”, arrival Sydney from Melborne 24.07.1876

- “Avoca”, arrival Sydney from Melborne 04.08.1876

- “Avoca”, arrival Sydney from Melborne 21.08.1876

- “Avoca”, arrival Sydney from Melborne 31.08.1876

- “Avoca”, departure Albany 13.09.1876

- “Avoca”, arrival Sydney from Melborne 26.07.1877

- “Avoca”, arrival Sydney from Melborne 20.08.1877

- “Avoca”, arrival Sydney from Melborne 15.09.1877

- “Avoca”, arrival Sydney from Melborne 28.09.1877

- “Avoca”, arrival Sydney from Melborne 27.10.1877

- “Avoca”, arrival Sydney from Melborne 15.11.1877

- “Avoca”, arrival Sydney from Melborne 06.12.1877

Transcript Illustrated Australia News 3 Oct 1877 – LOSS OF 5000 SOVEREIGNS

The detectives have received information by telegram that a box containing £5000 in sovereigns, which was transhipped to the s. China from the s. Avoca, had been missed from the former vessel on her arrival at Galle. It was thought that the missing specie had been by some mistake brought back by the Avoca, and on her arrival here on Sept. 4 the authorities subjected her to a rigorous search, but did not find any trace of the missing treasure. It appears that six boxes of gold, five of which were intended for England and one for Galle, were brought by the s. Avoca from Sydney in the charge of Mr. Roache, the second officer. On reaching Melbourne, the gold was transferred to the China, and Mr.Roache also went in charge of them. When the vessel reached Galle, the box was missed. No doubt is entertained now that a cleverly planned robbery has been carried into effect. The bullion room, in which the boxes of gold were kept, has been entered, doubtless by means of its proper key, as there is no sign of any forcible entry. The box, however, is not missing, but the contents have been abstracted in the coolest and most methodical manner possible. The gold was deposited in a bank box, which was itself securely packed in another, box belonging to the company, and sealed in the usual manner. The seals have been cut through, and the screws of the outer box taken out and subsequently replaced, while the inner box was boldly smashed to atoms, and the precious metal stolen. The thieves must have been thoroughly acquainted with the locale of the bullion room, and the routine observed on board the vessel. The Ioss was not discovered until the landing of the boxes, when the difference in the weight of the box in question led to an examination. It is generally believed that the deed was done after the transshipment of the gold in Melbourne.

Transcript The Mercury 4 May 1878 – FOR SALE

The Splendid New Yacht ” NEVA,” built by Macquarie, with all her sails and gear Complete. For further particulars apply to A. E. RISBY, 3937 Franklin Wharf flaw Mills.

Transcript from the The Argus 31 Oct 1878 – The Robbery of Gold from the Avoca

Shortly after the arrest of Martin Wiberg on suspicion of having stolen 5,000 sovereigns from the bullion room of the R.M.S Avoca of which vessel he was carpenter at the time, the press were in possession of certain information pointing to the fact that some other person holding a responsible position onboard the vessel at the time the offence was committed had acted in confederacy with Wiberg in abstracting the sovereigns from the treasure-room. Indeed, as a matter of fact, it became known that Wiberg, on finding that he had nothing to gain by remaining silent in the matter, made a full confession of the whole affair, implicating Elliston, the chief officer of the vessel, who appears to have acted as the prime mover in the robbery, having first taken Wiberg into his confidence. On the strength of the carpenter’s confession an information was accordingly sworn against Elliston, who is at present in England, and particulars of the affair were at once telegraphed home, with the view of acquainting the P. and O. Company in London in order that a warrant might be issued for the arrest of Elliston. For obvious reasons, therefore, an understanding was arrived at to the effect that the full facts ofthe case in connexion with Wiberg’s confession should for the present, at all events, be withheld from publication; but from what would appear to have been a breach of faith on the part of a section of the press, that understanding has been violated, and it is therefore considered that there is no longer any necessity to withhold further information in relation to the plain facts of the case. Wiberg’s confession, which may be taken for what it is worth, distinctly points to the chief officer (Elliston) as being the principal perpetrator of the robbery, and moreover that he had suggested the robbery to Wiberg, the carpenter, on the voyage of the Avoca from Sydney to Melbourne. Elliston, whose cabin was in close proximity to the bullion-room, had charge of the keys by which access could be obtained to the treasure, and having secretly apprised Wiberg of his intentions, Elliston fixed upon a rough and stormy night for the purpose of effecting the robbery. The working of the machinery was making a loud noise, and the passengers had turned in for the night. Taking with them a dark lantern, Elliston and the carpenter went down the hatchway to the bullionroom, and having entered with as little noise as possible, one of the six boxes containing the treasure was selected by Elliston. The outer case having been ingeniously opened and the seals around the inner box broken, Elliston handed the contents of the box, consisting of five canvas bags, containing altogether 5,000 sovereigns to Wiberg, who placed them in the chief officer’s cabin. The outer box was effectually closed again so as to avoid detection, and the door of the bullion room having been carefully locked again, the chief officer regained his cabin. No person on board observed the occurrence and the transaction was completed without causing the slightest suspicion. By a previous arrangement Wiberg went into Elliston’s cabin the following evening, and the door having been closed, the chief officer handed Wiberg one of the bags, containing about 200 sovereigns, as his share of the proceeds of the robbery. As Wiberg’s confession implicated the chief officer, it was considered absolutely necessary to keep the matter quiet, as Elliston’s wife and another relative who is conversant with the affair, were still in the colony, and it would only be reasonable to suppose that Elliston would probably be warned by cable of the confession made by Wiberg, in time to enable him effect his escape. It is, however, believed that the ends of justice will not be defeated by the undue publication of the facts of the case, since the officers of Scotland-yard will doubtless have been apprised of the facts ere this.

Trancript of Australian Town and Country Journal 2 NOV 1878 – PART OF 5000 SYDNEY SOVEREIGNS DISCOVERED

MELBOURNE, Monday.-Fourteen months since, in August, 1877, considerable excitement was caused by the announcement that on the arrival of the R.M.S. China at Point de Gaile, from Melbourne and Sydney, it was found that a great robbery of sovereigns had been committed. A number of boxes of specie were landed at Point de Gaile, and on examination it was found that one of those shipped at Sydney, which contained five thousand sovereigns, had been opened some time during the course of transmission, and the whole of its contents abstracted. Owing to unusual difficulties, it was found impossible to trace the treasure, or even to arrive at anything like a satisfactory opinion as to the perpetrators.

At that time the Avoca was engaged as the branch mail steamer between Sydney and Melbourne, and as such brought the Sydney shipments of specie and bullion to Melbourne, where they were trans-shipped, as it was supposed, to the Avoca. There was no evidence to show whether the transshipment of the case had properly taken place, consequently the question was whether the robbery took place on board the Avoca, or the China. This complicated matters to such an extent that the detectives found great difficulty in obtaining any clue to the perpetrators of the crime. Inquiries were made, however, the result of which revealed sufficient to convince the officers that the guilty parties belonged to one or other of the two ships’ companies, and they reported as much to the P&O Co., and at the same time the police authorities at all ports of call between Melbourne and Gaile were communicated with, but the inquiries instituted at Adelaide and King George’s Sound failed to elicit anything that could throw light on the matter. The company, however, acting upon the opinion of the detectives of Victoria, discharged a number of officers and petty officers of both ships. Although the robbery quickly sank out of public sight, the detectives never lost an opportunity of seeking such information as would assist them in further search. Inspector Secretan and Detective Mackay, the principal officers engaged in the case, persistently pursued inquiries. Among the persons discharged from the Avoca was the shim’s carpenter, a Norwegian named Martin Wiberg. Although all hopes of satisfactorily clearing up the mystery appeared to be at an end, the officers mentioned continued inquiries. They at last received information which led them to the conclusion that it would be no waste of time to watch the movements of this man Wiberg, as just prior to the robbery he had married a housemaid employed at au hotel at Williamstown. He appears to be a man of considerable energy, and besides being an excellent ship’s carpenter is well up in navigation and seamanship, as evidenced by the fact that after his discharge from the Avoca he procured a large open boat, put a tool box on board, and having supplied himself with necessary provisions, set sail by himself, and in that frail boat passed through the Heads. He steered an easterly course, doubled Wilson’s Promontory, and safely arrived at the mouth of the Tarwin River. He then steered up the river/and succeeded in finding a placé to his liking, his object being to select land and prepare a home for his wife. He discovered suitable land, took up two selections, one consisting of 100 acres, the other about twenty acres. The latter was situated quite close to the larger allotment on this land. Wiberg has been living there for some time. After erecting a tolerably comfortable wattle and dab house and clearing some land, he got his wife and child up to live with him. Inquiries as to the whereabouts and doings of Wiberg placed, Secretan and Mackay in possession of all these facts, and a clue as to his being the guilty person in connection with the robbery having been obtained elsewhere, it was decided to test the value of the information received. In order to do this it was necessary to proceed to Wiberg’s selection. Inspector Secretan, Detective Mackay, and Senior-constable O’Meara started more than a week since, their destination being the selection of the suspected man. This was found to be situated in a wild, almost inaccessible part in South Gippsland. Tarwin river empties itself into Corner Inlet, and is a stream of rather inconsiderable proportions. The officers had information that Wiberg was a most determined man, and that from what had been seen of his house and contents, it was evident that if an attempt was made to capture him he would resist, and from the nature of the country, and the knowledge he has acquired of it, he would have a fair chance of escape. The officers decided to proceed to the spot, but were saved much anticipated trouble for on the second day out, after crossing Powlett River, they camped in the afternoon, when the man they wanted rode up quite unexpectedly, and was at once recognized. After a short conversation, he was suddenly arrested. On searching him a number of sovereigns were found in his possession. He stated he had intended investing them in a craft to trade between Melbourne and Tarwin River. The party then proceeded on to his selection, having first taken the prisoner back to Griffiths’ Point, and lodged him in the lock-up. Then, in order to reach the selection, it was found necessary to cross a number of creeks, some of which they had to swim. On arrival at the house of the prisoner a minute search was instituted by the officers, who were once more successful, and discovered another parcel of sovereigns. These were secreted in the ends of a carpenter’s plane about three feet long. A hole had been bored in the plane to the depth of about two feet from one end, the sovereigns being carefully placed in the hole and neatly plugged up. The plane when found was lying about among other tools. Altogether about 200 sovereigns are recovered. The detectives are sanguine as to being able to recover nearly the whole of the missing treasure. From all the circumstances it is evident that the theft was committed during the passage of the Avoca to Melbourne, the prisoner (Wiberg), by some means, gaining ad mission to the treasure room, and opening a box which contained the sovereigns. He must have extracted them, carefully supplying their place with some heavy material, and closing the box up again so neatly that it could not be noticed that it had been tampered with. On arriving at Melbourne he had ample opportunity to remove the booty, as the Avoca remained here some time. The prisoner was frequently ashore, and suspicion could not have been aroused, as the robbery was not reported until a month afterwards. Wiberg therefore easily removed the concealed sovereigns. Prisoner was left in the lock-up at Griffiths’ Point until he could be taken before the local bench, and remanded to Melbourne, Senior constable O’Meara remaining behind. Inspector Secretan and Detective Mackay returned to Melbourne on Saturday. Prisoner was taken before the magistrates, and remanded to Melbourne. He arrived in the metropolis this morning in custody of Senior-Constable O’Meara, and was at once taken before the City Bench, and remanded for a week. He has made a confession which, for the ends of justice, it is necessary to suppress for the present.

MELBOURNE, Wednesday.-The man Wiberg, in charge for the Avoca gold robberies, confesses that the officer was the principal offender, and allowed him access to the bullion-room. He pays he got only five hundred pounds for his share.

Gippsland Mercury 25 Feb 1879 – “THE WIBERG INQUIRY”

THE WIBERG INQUIRY, The board appointed to inquire into the circumstances under which Wiberg effected his escape from the detective officers at the Tarwin in December last proceeded to the scene of the escape this week. The party consisted of Messrs. R. Richardson and J. Mirams, M.’sL.A., the secretary to the board, Mr Inspector Secretan, and Detectives Duncan and Mahoney. The accommodation for travellers at the Tarwin is of a rough and ready kind, and Mr Black, the owner of the station that extends for many miles along the beach and inland, kindly sent an invitation to the members of the party to partake of his hospitality for the night. The invitation was gratefully accepted. Prior to proceeding to Mr Black’s station, which is about four miles from the site of the escape, a careful survey was made of the ground over which the chase and loss of prisoners took place. The bearings taken and the general information gleaned fully justified the trouble taken by the board in visiting the site. It was ascertained that the measurements given by the witnesses as to distance were very much in error. The total distance run Mahoney from starting point to the spot where he was lost was about 600 yards. The place where the first fall took place was forty yards from the starting point instead of five. At forty yards from the start there is a drain large enough to account for the two men falling, and at this point Mahoney actually touched the prisoner with his hand. On rising, almost simultaneously, the two med had a fair, straight race, over good level but slippery ground. The frequent falls are easily accounted for. But by rapid degrees the prisoner ran away from Mahoney. He gained so much, in fact, on his competitor that the retarding influence of having to creep through a strong wire fence was not enough to enable Mahoney to overtake and arrest the fugitive. In the first place he found himself to be, according to his own showing, a far slower runner than Wiberg on clear level ground. During their investigation the board took the evidence of several witnesses, and they have ascertained many important facts. Amongst other information they found that Wiberg was entertained on the day of his escape by a man named Christopher John Fisher, Wiberg arrived at his hut shortly before sundown, and asked for food and drink. He (Fisher) gave him bread, meat, tea and tobacco, allowed him to cut of his whiskers with a pair of shears, to take away and old hat, and also gave him some provisions. Though Fisher knew Wiberg had escaped from justice he made no attempt to arrest him, though he had a gun and could have been assisted by a man and a boy who resided in the hut; nor did he inform the police of the fact until a week after the event. The evidence procured by the board is in detail valuable, and an important addition to the information previously elicited and published.

The Telegraph – 11 Mar 1879 – “THE AVOCA ROBBERY” – (Wiberg spotted on the loose)

The Avoca Robbery.— In reference to the prisoner Wiberg, who, after being arrested by the police for the Avoca gold robbery, escaped from their custody, we find the following in the Hamilton Spectator: -“The police imagine all sorts of things about Wiberg. Some think -doubtless ‘the hope is father to the thought’ -that he has died of starvation in the bush; other fear that he has made his way to Melbourne, or one of the seaports; but, according to the following information, received from an old resident of Hamilton, all these surmises are incorrect. Wiberg is still at large, and at his ease in Gippsland. Our informant, who is a surveyor, now camped on the Droin track, writes under date 21st February: -‘Even in the wilds of Gippsland there is sensation. Last evening, whilst at tea, I had a very strange visitor in the person of Martin Wiberg, the notorious gold robber. He appears to be well on the track of the police, instead of their being on his. It was about 5 o’clock when two horsemen passed my camp, who, by their cut, I judged to be policemen; but, shortly after, Wiberg came up, and informed me that only one was a “peeler”, the other being a Melbourne detective. So close was Wiberg on their heels that they had not been gone ten minutes when he arrived, dressed in white, accompanied by another man, and asked for a drink. I at once saw that he did not know us, although he might have done, as he rowed us up by the Tarwin in July last, so I turned the conversation on the police and Wiberg. Upon this my visitor became excited, and asked several questions as to his own height, color of whiskers etc, doubtless to mislead me, but did not stay over two or three minutes. The pair then started off, not a good round gallop, but at a trot, along the track, the companion leading the way. There were six men around the camp – five besides myself; and I was well armed, having a loaded revolver on me at the time (an article I always carry here), and it would have been a very easy matter to have secured both Wiberg and his companion. But “le jen ne vant pas la chandelle” (“the game is not worth the effort”). Why do not the Government offer something like a reward? What is a paltry £50? He is now within twenty-four miles of my camp; and if your noble guardian of the police, Sergeant Richards, were sent up I could lay him on. I am told the policeman and detective returned back by the Drouin track to-day, but I did not see them.

South Bourke and Mornington Journal 21 May 1879 – “THE AVOCA GOLD ROBBERY – RE-ARREST OF WIBERG”

The robbery of 5000 sovereigns from the mail steamer Avoca will long be remembered as one of the most sensational thefts perpetrated in this part of the world, because of the succession of strange incidents which followed the robbery, which was committed on board of the Avoca between Sydney and Melbourne, or on board the China between Melbourne and Ceylon. For some time the circumstances surrounding the robbery were enshrouded in mystery, which was eventually overcome by Detective Mackey, who obtained information which led him to believe that Martin Wiberg, who had been engaged in the Avoca as ship’s carpenter, but had subsequently been discharged, was the culprit. Acting on that information, Detective Mackey, with Inspector Secretan, proceeded to the Tarwin river, where Wiberg had taken up a selection, and arrested him. In his hut they found a quantity of the stolen sovereigns, and the prisoner was then brought to Melbourne. Soon after the arrest he made a statement in which he asserted that he and Elliston, the chief mate of the Avoca, had effected the robbery and shared the plunder. Believing that his story was a true one, Detective Mackey proceeded to England to arrest Elliston. He succeeded in the object of his visit, but Elliston was discharged because of the want of evidence to warrant his being sent to Victoria, and Mackey had to return to Victoria without him. In the meantime Wiberg, professing to make a clean breast of the whole affair, professed his ability to point out where more of the stolen property had been secreted in the Tarwin River. Inspector Secretan believed his story, and took the prisoner to the Tarwin river, he being accompanied by Detectives Duncan and Mahony. The story of his escape whilst searching for the hidden sovereigns is well-known, and since that time no positive intelligence concerning the escape has been made public, although as a matter of fact the detectives knew some thing concerning his movements, and were aware that he had not succeeded in leaving the colony. It was not, however, until about three weeks ago that that opinion was formed, and it was the action of Wiberg’s agents in Melbourne which first caused the surmise. The capture was effected near the Eagle’s Nest, Cape Patterson, on Friday last, by Detective Edelston and Mounted Constable Taylor. These officers were sent to that part of the country more than a fortnight ago, and every credit is due to them for the manner in which they per formed their duty in searching the country, undergoing, as they state, great privations After searching thirteen days the vigilance of Edelston and his companion was rewarded. On Thursday they discovered footprints in the sand of the sea shore near Anderson’s Inlet, and these footprints led them to form the opinion that the person who had left the marks behind had swum across the inlet towards Cape Patterson Suspecting, that they were on Wiberg’s track, they on the following day went to the other side of the inlet, and whilst searching for further tracks they first heard and then observed a man walking through the scrub. Immediately they sought concealment, and on walked Wiberg—for it was he—not suspecting danger; but when within about fifty yards of the ambush he evidently caught sight of the stooping form of Taylor, and, somewhat to the dismay of the police, he turned and fled along the sea shore. Edelston and Taylor seeing that at once gave chase, and Wiberg gave them a taste of his abilities as a pedestrian. He sprang down a cliff about four teen feet, and made for the water, and his pursuers, thinking he had intended to seek safety by swimming out to sea, he being reputedly an expert swimmer, fired three shots at him. The discharge of the firearms, followed by the whistling of the bullets, had the desired effect, and Wiberg, throwing up his arms, called out, ” I give up.” Glad of the opportunity, Edelston, with the assistance of his companion, soon handcuffed the prisoner, and took him to Mr. Laycock’s, on the Tarwin River. There they remained all night, Wiberg being closely watched during that time. He was not in the least dismayed by his arrest, and laughed and jested. But during the whole time that he was in the custody of Edelston and Taylor he said not one word which would tend to convict him of the robbery from the Avoca, or an admission that he had falsely maligned his chief mate, Mr. Elliston. There was no chance of his escape, because wherever he moved he knew that, besides being handcuffed, he was covered by the loaded revolvers of his captors, who profited by the lesson he had taught Inspector Secretan and his party. He was brought before the Griffiths’ Point magistrates pro forma on Saturday, and was remanded to appear in Melbourne on Saturday next. From thence he was brought to Melbourne by the Phillip Island coach, and the great public interest which the robbery has created was evinced by the large crowds of spectators who assembled at Prince’s bridge to get a glimpse of the man who had robbed the mail steamer of £5000, and had subsequently outwitted the detectives. About 1500 people awaited the arrival of the coach at Prince’s bridge, fully 2000 more stationed at the lock-up, and opposite the Albion Hotel, but the curiosity of the public was doomed to disappointment. The coach was met at St. Kilda by Sub Inspector Secretan and Wiberg was transferred to a buggy, and was brought to the Melbourne Gaol via Richmond. He was dressed in very “seedy”‘ garments, and, indeed, his general appearance indicated that he had slept in the same clothes ever since his sojourn in the Tarwin district. He seemed to be in excellent spirits, and the fact that he appeared to have grown stout since he was last seen in Melbourne indicates that he has not been starved. Sub-inspector Secretan refused to permit the prisoner to be interviewed, and the governor of the gaol also declined to grant a similar request. Reliable information has been obtained, which serves to show that Wiberg was arrested upon information first obtained in Melbourne. About a month ago the schooner Patrion was chartered in Melbourne by a man named Pearce to carry provisions to the vicinity of Waratah Bay. When just outside of the Heads the schooner was found not to be seaworthy, and the goods which she was carrying were transferred to the small steamer Gazelle and were afterwards landed at certain lime kilns. The owner of the Patrion subsequently sued Pearce in the County Court for £100 on a breach of agreement. Certain circumstances then came to light, which evidently caused a suspicion to be formed that the Patrion had been engaged in the interests of Wiberg. These suspicions in turn provoked enquiries, which resulted in the discovery of the fact that the sum of £’1000 had been transmitted by Wiberg to Melbourne for the purchase of a schooner. Feeling confident that he was still in the Tarwin district, Sub-inspector Secretan acting upon advice, sent two officers and a black tracker to Stockyard Creek to keep a look-out on the Waratah side of the river, and about two weeks ago he despatched Messrs. Edelston and Taylor to the Tarwin to keep watch on the Liptrap side. He also sent two men to Waratah Bay to prevent Wiberg from escaping by vessel. The success of this movement is demonstrated by the arrest on Friday of Wiberg. Immediately on the news becoming known in Melbourne, Sub-inspector Secretan and Detective Mackay acted upon information, and searched the house of a well known resident of Emerald Hill, where they discovered 800 sovereigns in a barrel of tallow which had been designed, in the first instance, by Wiberg herewit to purchase a vessel to make good his escape. They also visited the house occupied by Mrs. Wiberg, who, they were informed, had received 50 sovereigns from the agent already referred to. Mrs. Wiberg handed the police, after much hesitation, 38 sovereigns, stating she had expended £12. An official report has been sent to the Detective Office.

Trancript from The Telegraph 25 MAY 1879 –

Joseph Penroc, the master of the cutter Petrel, has been arrested In Melbourne charged with aiding and abotting Wiberg, And being accessory after the fact to the robbery of the 1,000 sovereigns from the P&O Avoca. It is said that the police have discovered a portion of the stolen sovereigns at Williamstown, where they were planted, It Is believed by Wiberg.

Transcript from The Argus 10 JULY 1879 – PROCECUTION OF WEIBERG AND PEARCE.

The prosecution of Martin Weiberg and Joseph Pearce, the former for stealing 5,000 sovereigns, the property of the P. and O. Company, and the latter for being an accessory after the fact was continued in the City Police Court yesterday before Mr Call, P.M., and a Bench of magistrates.

Mr C A Smyth conducted the proceedings on behalf of the Crown and Mr Purves appeared for the defense Mr Richards watched the proceedings on behalf of the witness Captain Walker.

The first witness called was John Davis, master of a small steamer named the Gazelle trading lately been seen Melbourne and Waratah Bay, who deposed,- I know the prisoner Pearce. He was a passenger on two occasions, the first time about the 7th or 9th of April last. Before that I had seen him in Williamstown. He said he had some freight to go down and he sent it down. It looked to me be meat, bread and potatoes. It was to be delivered at Waratah Bay. It was addressed to Brown and Pearce. Brown took delivery. Pearce was there too. Pearce complained of poverty and asked me to give him a passage up with some skins. He said he had no money but that he would work his passage. I took him to Melbourne. I next saw him in Melbourne On my return to Waratah Bay. I heard something and when I came next to Melbourne I spoke to Pearce This would be about the 21st or 22nd of April. He came alongside the vessel at the south wharf. I said, “you were a pretty fellow to complain of poverty when you came up with me, and had 800£”. He admitted first having, 500£, and afterwards in conversation he admitted having the £800 he did not tell me where he got the money. I did not ask him for any money. The next occasion I saw Pearce he was a passenger, on the 1st May to Waratah Bay, vid Loutit Bay. Through stress of weather I had to come back to Queenscliff for shelter. During the time at Queenscliff on shore, I had some conversation with the Pearce. He said he took Wiberg from a cave close by the lime kilns while the detectives were searching the house Brown was in ; that Brown put him there and gave him food. On our arrival at Waratah Bay, there was a small box, which was addressed to Brown on board. It was taken ashore with some letters to the manager there. When the boat came alongside, Pearce went up the wharf. He left this small case to come up in a truck. During the time this case was on the truck coming up four police-officers came on the beach. Later in the day in the house of the Manager, Pearce was saying how nicely he had done the police, and he took from his pocket a likeness and a letter. The letter was addressed “For Jimmy” and I believe was for Weiberg who went by the name of “Jimmy Morgan”. The likeness Pearce told me was of Wibergs wife and child. Pearce had them concealed in the lime bags before he was overhauled by the police. Pearce opened the box addressed to Brown, who took from it a pair of shoes and a pair of garters a parcel of hair dye, and a parcel of acid. I asked Pearce what the hair dye was for and he said to disguise Jimmy. The acid, he said was to remove the marks from his person. Pearce also had a revolver and a bag of cartridges. He did not say anything about them. The revolver produced is the same. About the 11th or 20th May, while out hunting with Pearce, I asked him how he became so foolish as to let Mrs. Brown wash the £800. He said he washed it himself after Mrs. Brown was in bed. I said, “That is a nice thing for you to be there after she was in bed.” No more was said on the subject. I was in a tent at Liptrap belonging to Pearce or Harvey. The last time I was there I was sent there. I never went to meet Weiberg. I took the revolver to the Liptrap. I was shooting with it. Nothing was ever said by Pearce about taking Weiberg to sea. I never had any conversation with Pearce about taking Weiberg away. I never told the detectives that such was the case. I only took Pearce to Melbourne once and once to Waratah Bay. The Brown I speak of is a man employed at the lime kilns at Waratah Bay. I do not know that Pearce lodged at Brown’s place.

William Mathews, ship and boat builder, Williamstown deposed -I own the cutter Petrel. I know the prisoner Pearce. I recollect seeing him in the month of February last I do not remember the exact date I never saw him before. He came to my house about 7 or 8 o’clock in the evening and asked me if I owned the Petrel. I said, “yes I do.” Pearce said, “We want a craft to go down to Waratah Bay, and if you come down to Mr Crawcour’s in the evening I will make arrangements with you. I went to Crawcour’s and Pearce was there. He asked me how much I wanted for the hire of the vessel for a month I said I did not know hardly but I thought about £10 a month. He said he was willing to give that. I said, “You will have to give me security for the worth of the craft – £85.” Mr. Crawcour was standing there and said he thought £75 was enough. I agreed to that. Mr Crawcour then wrote out an agreement to that effect. I have not got the agreement. The last I saw of it was in the County Court, when I sued Mr Crawcour for the amount. They took charge of her at the date of the agreement. Pearce and Crawcour made some remark about and a lady passenger. They took the craft away in and about a fortnight afterwards. Pearce and Crawcour came again and returned the craft. Pearce said the vessel was leaky and the chain rotten. He said they had got as far as Queenscliff.

Jane Brown wife of John Brown labourer, employed at the lime-kilns in Warratah Bay deposed -I was lately living at Emerald-hill. I know prisoner Weiberg’s wife now. She lived with me for the last eight weeks. I know the prisoner Pearce. He had been back and forward to my place. I saw Pearce about eight or nine weeks ago. He had a bag with him, like a guano bag. He put it down on the floor. He did not say what was in it. I asked him, and he said he had “sprung a plant” and afterwards I saw him washing some sovereigns in a tub. I could not say how many he had. I told him to take them away and he did so the same evening. I also saw him with some rolls of paper in the shed. I could not say how many. That was on another day. I know Mr Crawcour by sight. He came to my house with Pearce. I think that was before he brought the bag. Crawcour went into my shed with Pearce, and I saw Crawcour take away the rolls of paper. They looked as if they had money rolled up in them. I did not say just now that the papers contained sovereigns. I only saw the outside.

Mr Purves objected to the prosecution endeavoring to make the witness say that she saw the sovereigns.

Mr Gill.-The witness is giving her evidence very unsatisfactorily.

Mr Smyth.-You have full permission to cross examine her.

Mr Purves.-I never heard such a permission given without its being asked for. The police magistrate throughout this case appears to have made up his mind what the evidence ought to be.

Witness to Mr Purves -I have told the truth.

James Hill deposed. -I am residing with my father, a grocer at Emerald-hill. I know the prisoner Pearce. He is a customer of ours. About the 15th of March last he came to me and ordered some goods to be sent to Williamstown in the Gem. He ordered them- so far as I know- for himself. There were potatoes, flour and rice-about £3 worth. He did not pay for them. He said he would be up again from Williamstown. At that time Pearce spoke of Harvey. Pearce said he would call again and settle. He said there was a lot of skins on the pier at Waratah Bay and that when they were sold he would pay. I understood from Pearce at this interview that the things were for Brown who was a mate of Pearce’s, at Waratah Bay. Two or three weeks after Pearce came again and ordered some more goods for Waratah Bay to be sent to the wharf to the Gazelle. They consisted of tea and other groceries, about £8 worth. Pearce did not pay then. He said he would pay when the skins were sold. Two days after Pearce called I spoke about payment for the goods. He said his father had sent him out money from home, and that I need not trouble he had plenty of money. In the course of conversation, he told me he had sprung Weiberg’s plant, that he had watched the detectives down there, that it was a very lonely part of the bush, and that he had followed the footsteps to a tree. That on examining the tree he saw an auger hole; that he probed the ground with his ramrod and that he found something hard. He dug it up, and found there were 800 sovereigns in it. In a tin I think he said. I asked him if he know Weiberg. He said, “I never saw him, he must be dead. He could not possibly live in such a place as it is down there.” I asked Pearce what he was going to do with the money. He said he was going to buy a craft when it had all blown over and go into the potato and onion trade. On the first occasion Pearce paid me go £5 off Brown’s account. I have told all I remember up to that time. After Pearce’s trip in the Petrel, the next time I saw him he told me he was going to take an action about the boat. He said he was going to fetch up the sovereigns he had found in the plant. The next time he told me he had walked overland to Waratah Bay, and had come Back in the Gazelle. He came up to me on Saturday night and told me that he had got the sovereigns up all right, and he gave me one on that occasion he said they were in a clothes bag, with his dirty clothes, knocking about the deck of the Gazelle. When he gave me the sovereign he said, ” There is one of them. He gave it to me as a curiosity. He asked me to change the sovereigns for him at the same time I gave him silver for one and a note for the other. I next saw him the following week at our shop Pearce Rind, “I have got the sovereigns up all right, they are down at five Browns I said!, What are you home to do with them ‘ He said, “I thought of having a house in Williamstown,” and then he asked me if I would take charge of the sovereigns. I said, “I don’t wish to have anything whatever to do with it. If you bring anything to be left in my charge you can have it whenever you want it.” I said if there was anything wrong about if I would hand it over to the detectives immediately. Pearce said,” There will be no fear of anything of that sort. I found the money it is as much mine as anyone else’s. There is no suspicion about my having it too gave me nothing I, then. A day or two after he brought up a parcel under his arm. It was about a foot long rolled up in a newspaper. He placed it on the counter and said,” Take care of this till I come back. I asked him if he was going to leave it in that way. He said, “Oh put it into a bag.” I got a sugarmat. He put the parcel in it and it was tied up. I threw it into the office. He did not say on that occasion anything about washing them. On one occasion he told me he had brought them up in fat and had a hard job to wash them as he had to do it in the night, in case Mrs. Brown should see them. I threw the parcel in the bag into the office. I did not notice its weight. About 1 week after he came again to the shop to me and said, “I have had a chat with Detective Mackay”. I said “You had letter take your parcel away if you are talking to them, I am afraid there will become trouble over it”. Pearce said, ”It is all right there is no fear of anything happening.” Weiberg’s name was not mentioned after the first interview. The second night Pearce called after telling me about Detective Mackay; he called me to the door, and said “I want £50.” I said, “I cannot give it to you.” He said,” It is alright; let me have the parcel and I will get it myself.” He said he wanted it for Mrs. Weiberg, that he had met her in Lonsdale street, and that she was almost starving. I said he could not have it then as my brother was in the office. He returned again in the evening; we went into the office. He opened the parcel and he took some roll out and took them away I could not see what they contained. He said they were sovereigns. He gave me two rolls. He said,” These are for yourself.” I took them. They contained 40 sovereigns. I changed them into notes. I afterwards took out other rolls in which there were 60 sovereigns. I changed them into notes as well. I did not see Pearce after he left that night. The next thing about the money was when Mr Secretan and Detective Mackay came on the 10th May. I then handed him the parcel which contained 256 sovereigns. They were all over fat. I also handed them the £100 in notes which I had changed the sovereigns for.

Michael Crawcour, pawnbroker, Williamstown deposed,- I have known the prisoner Pearce two or three years. About March last I first saw him in connexion with this case at my place of business. He was by himself. He came in and I asked him to have some tea. He said,” I have brought up some money at last”. I said,” Where is it?” He said,” At Brown’s, on Emerald-hill. He said,” From what I learned from Weiberg, I went to his selection and on the edge of a plain near a large gumtree after looking about for some time I saw a place where the grass was much greener than the other places. I dug there and cut up a billy and 300 odd sovereigns in it.” He saw alongside it there a shipwright a slice-a kind of broad chisel. I then asked him where was the money. He said at Brown’s at Emerald-hill. I knew her husband well. I arranged with Pearce. I don’t know if it was exactly at that time. He told me he had got Weiberg down at Waratah Bay, planted in the scrub and that he (Pearce) was to take him to Callao. Pearce asked me to look after a vessel for him that Weiberg had agreed to give him £1000 and the vessel for himself at the end of the journey. Pearce asked me if I would change the money if he brought it up. I said I would. He asked me what I would charge him and told him 10 per cent. Pearce said, If you will I will bring them up. He said that Weiberg had the whole of the £5000; I went to Mrs. Brown’s with with Pearce on Sunday morning. Mrs Brown was there. Pearce went into a shed and brought out some parcels rolled up each about the size of a pound’s worth of silver and handed them to me. I was going to Windsor When I got there I opened the rolls and I found this contains 300 sovereigns and odd. Pearce did not go with me to Windsor. I have not those sovereigns still; they are changed and the balance I gave to Mr Secretan (The £46 cheque referred to). The sovereigns were all dated 1877 and bore the wreath brand. I cannot say where they were struck. Pearce also said that he and Harvey had been keeping Weiberg until they could keep him no longer as the provisions ran short that then they had a row with Weiberg- and Pearce said to Weiberg,” If you have the money had better go and get some; we cannot afford to keep you longer. That Weiberg started for the Tarwin and was away two or three days, and that they met him at the head of a gully. They gave him, he said, a feed, as he was nearly starving, and Weiberg gave him 500 sovereigns as a New Year’s gift. Pearce told me to take what they owed me. That was a joint account of Brown’s and his and their separate accounts, and to keep the balance until they wanted it. Pearce came to me again and said he had brought up 800 Sovereigns. This was some weeks after. He said they were rolled up in some tar and fat in the middle of his swag and that he had taken them to Mrs. Brown’s. He said Weiberg had given them to him to bring to me for chance. Occasionally he came with one two or three sovereigns and asked me to give him notes for them which I did I asked him where was the balance. He said the were not cleaned he would bring them over. At last he came with 10 and said he wanted them chanced to send £10 to Harvey. I understood Pearce to say he wanted this money to buy a vessel. Pearce wanted a boat to take provisions down and he told me one evening that he had engaged the cutter Petrel. I said, “What did you agree to give?” He said £10 for the use of the vessel for four or five weeks. The witness Mathews came to me in the evening and said he wanted an agreement from someone he knew as he did not know Pearce. I drew up an agreement undertaking to give Matthews £10 for the use of the vessel and £70 if she was not returned in the same state as we took her. Some days before Pearce left the last time he gave me two lists of things he required, including soap, boots, shoes, a felt hat, a revolver, caps some acid (which he said was to the out a mark on Weiberg’s hand), some hair dye (Pearce said for Weiberg), two pairs of garters. The revolver produced is the same. Pearce said it was for Weiberg too. I had these things in my place and I sold them to Pearce. Pearce brought up letters. He said they were for Mrs Weiberg from her husband. He told me that he brought up £250 for her. The next time he said it was only £50. He said it was in the £800 he brought up. Pearce gave me a letter once describing a place on the banks of a creek near a waterfall at a place they call Bear Gully. He said he had 500 sovereigns there in a fruit bottle and that if anything happened to him I was to dig there and divide the sovereigns between myself and Brown. After he brought the £800 up he said the 500 was amongst them; and I said, “Then this letter is no use now?” He said, “No,” and took it from me and tore it up.

George Edward Walker master of the steam tender Sprightly, deposed -I have known the prisoner Pearce for about two years. I saw him in March last. He asked me if I would take charge of a vessel he was about buying I said, “No”. He did not say where she was going to. I saw him in the meantime off and on. At the beginning of April last he came to my house. He was talking generally and then he said he would lend me £300 to buy a house with. I never asked him for a loan. I was to pay him interest at 7 per cent and I was to pay him off by monthly instalments. I had been speaking to him and telling him I was going to buy a house. The only security I was to give him was an agreement to pay so much a month to his credit at the bank he gave me the money on the 16th April at my house. It was 300 sovereigns. He did not say where he got them. I merely counted them and handed them to Mr Richards who drew out the conveyance of the house I bought. On one occasion I asked Pearce if he had seen or know anything of Weiberg.

He said “No,” and added- “Weiberg will never be taken alive.” The house was conveyed to my wife I handed the deeds to Detective Mackay. They are the same now produced.

Detective Edelsten deposed – On the 16th of May last, myself and Senior Constable Taylor arrested Weiberg near the Eagle’s Nest. I got eight sovereigns from the witness Harvey, and also a revolver at Harvey’s hut, where Weiberg was staying. I got the rifle ammunition, and telescope produced from Mrs Laycock.

Senior Constable Francis O Meara deposed,- I was with Inspector Secretan Detective Mackay, and Senior Constable Taylor when Weiberg was first arrested in October last.

Senior-constable Harold Henry Taylor deposed,- I was present when Weiberg was first arrested, and I witnessed the confession signed by Weiberg, produced, and marked as on exhibit. This closed the case for the Crown.

Mr Purves submitted that a prima facie case had not been made out, as no proof had been given that any sovereigns had over been stolen, and a confession could not be made binding without the production of the corpus delicti. Confessions of crimes never committed were by no means unfrequent, as it was a peculiar phase of the mind of some persons to confess enormities which had no existence in fact. There was actually no proof whatever that any sovereigns had ever been stolen at all. The nearest approach to that conclusion was the evidence of the bank clerk at Sydney, but he could only prove the existence of five bags which he believed to contain money, but he did not know what. He could not prove they were sovereigns, and although the Crown tried to get that in, they failed. Even had he been able to speak to the contents of the bags, his evidence had no weight, as the bags were left in the treasury after he saw them in the second place, presuming the sovereigns had been stolen, they did not belong to the P. and O. Company as set out in the information. They belonged to the Oriental Bank. The mere fact of a man entrusting his tools to a carrier who was responsible for them if they were lost did not alter the ownership. He did not presume, however, that the Bench would assume the responsibility of deciding a point of law, but they could not refuse to deal with matters of fact. He presumed they would not deal in that respect with regard to Weiberg but as far as Pearce was concerned there was no evidence against him. In the last place there was no evidence of the larceny of the sovereigns and even if there were, there was no evidence that Pearce had anything to do with it. He was not charged with harboring an escaped prisoner, but with being an accessory to the robbery after the fact. He could not be charged with harbouring a prisoner, as there was no doubt in a legal mind that Weiberg was not in legal custody when he escaped. Weiberg was committed to gaol to be kept there until tried, and the detectives had no more authority to take him to the Tarwin than they had to take him to the theatre. The only evidence at all against Pearce was that of Harvey, an accessory, and, as the Bench must be aware, the evidence of an accessory, uncorroborated was not sufficient. As far as Pearce was concerned, no guilty intent had been shown; and although the manner in which he had acted might to a certain extent be collateral evidence of guilt, still there might be many other reasons which actuated him. Pearce had been immensely prejudiced by the fact that he was standing beside Weiberg whilst all the voluminous evidence was given against the latter prisoner. If Pearce was guilty, were not the witnesses Harvey, Hill, Crawcour, and Brown in an exactly similar position? For they came forward to give their evidence and what did it amount to? Simply that Pearce had received Weiberg after he had escaped from illegal custody, and that he wished to remove him from the country. He submitted that the evidence did not warrant the committal of Pearce for trial.

Mr Call intimated that the Bench had decided to commit both prisoners for trial.

Mr Purves then submitted that the prisoners should be admitted to bail—Weiberg in a substantial amount and Pearce in moderate sureties.

Mr Smyth pointed out that one of the prisoners had already once escaped from custody, and that if either were admitted to bail they might secure the £3,000 or £4,000 which there was reason to believe was still planted in the bush.

The prisoners were formally committed for trial, and having been cautioned in the usual way, reserved their defence. The Bench after consultation decided to accept bail for Weiberg in two sureties £1000 each, and for Pearce in two sureties of £250 each.

Transcript from the New Zealand Herald 26 JULY 1879 – “MARTIN WIEBERG, THE GOLD ROBBER”

The trial of the above clever and ingenious scoundrel ended this week in the Supreme Court of Victoria. The circumstances of the ease are peculiar, aid, even at this stage, will bear repetition. The offence with which he was charged was that of robbing one of the P&O Company’s boats of a consignment of 5000 sovereigns, shipped by the Oriental Bank, while the vessel was on the passage from Sydney to Point de Galle.

A second charge of receiving stolen goods was also laid, and it is upon the latter that he has been sentenced to five years’ imprisonment. All efforts failed to trace the thief at time, but, on evidence collected by an officer of the P. and O. Company, Mr. Elliston (the Chief officer of the Avoca), and Martin Wiberg (the carpenter), were both dismissed for alleged neglect of duty. Elliston went to England, but Weiberg married a barmaid in Melbourne, and took up his residence as a selector on the Tarwin River, Gippsland, announcing his intention of making there a home for his young wife. A less hopeful spot for agriculture it would be hard to find, and into that desert Weiberg departed taking up a selection next to that of one Laycock, who owned the one inn which adorned the sterile settlement of Baas. From “information received,” the police went to watch the ship-carpenter who is so kindly disposed towards agriculture. A raid was made upon his hut, and 200 sovereigns found secreted in a hollow log. Another plant was discovered by Weiberg’s servant girl in a bar of soap, which she was accidentally cutting in two for household purposes. To her astonishment, the knife struck something hard, and, on looking for the cause, she saw the shining gold pieces wedged in the soap, and she took the money to her apparently astonished mistress. Other “plants” were discovered in various localities.

Weiberg, on being brought to Melbourne, confessed his guilt, and blamed Elliston, who, he said, bad given him a bribe of £200 to do the deed. He explained also to the police, the method by which he accomplished the robbery, and stated that there were four different ways by which he could reach the bullion room of the mail steamer. By and by he told the detectives that his share of the plunder came to £1800 more, and that if he was taken back to his home in Gippsland, he would point out where the money was concealed. The police closed with the offer, Inspector Secretan and two of his men (one Mahony, being specially chosen on account of his fleetness of foot) started with the confiding prisoner to Gippsland. The Tarwin was reached, and on the morrow the penitent thief declared he would bring up from its gloomy depths an iron pot, containing the missing gold. A boat was procured, and Secretan descended first into her. The bank was steep and slippery, the current strong, and Duncan, watchful for the safety of his officer, took bis eye for-a moment from the prisoner. Wieberg was unhandcuffed, “so that he might give the better assistance,” and a blow of his elbow in, the diaphragm of the fleet-footed Mahony, left him an instant free. Then began a race between the constable and the thief; but Weiberg knew the bush, and having the advantage of a start, was soon out of sight. A howl of public indignation was the result of this fiasco, and public opinion, as well as the report of the I Board of Inquiry, half-hinted at the current rumours that the police had been “provided for.” These statements put the detective force on its mettle. The first trustworthy information ascertained by the detectives concerning the movements of Wiberg after his escape were drawn from the circumstances disclosed in the case of Matthews v. Pearce, in the County Court. Pearce, was a man well known to the police as a hunter. For some time he was a hunter at King’s Island, and subsequently appeared as a hunter on Tarwin River. His skins were sent to Melbourne, and he appears to have had dealings with a pawnbroker, named Crawcour, at Williamstown. With Mr. Crawcour it is alleged that Pierce entered into certain arrangements for the purchase of a vessel, and deposited with him the sum of three hundred sovereigns. It was from Crawcour, and not Mr. Matthews, the owner, he had chartered the cutter Petrel, which was subsequently found to be unseaworthy. After the case in the County Court in Melbourne, a member of the detective force saw Crawcour, and learned from him the nature of the transactions between himself and Pearce. The further intelligence was afterwards obtained that Pearce had given the son of Mr. Hill, hotel-keeper, at Emerald Hill, a further sum of 800 sovereigns. Young Hill, after a little difficulty, disgorged the money he had received. Inspector Secretan and Detective Mackay paid a visit to Mr. Crawcour at Williamstown, and there obtained s portion of the sovereigns Pearce had deposited with him. Crawcour made a statutory declaration concerning the circumstances under which Pearce gave him the money. Hill did the same, and they were called as witnesses of the Crown in the charge that will be preferred against Pearce, who has received a year’s imprisonment. The detectives, having been put on their mettle by the expression of public opinion, exercised a constant supervision over Weiberg’s wife, who lives in unassuming grass-widowhood at Emerald Hill. It was known that she had £50 in the house, and was suspected of possessing more. In consequence of further intelligence, another detective was sent again to Gippsland on the track of the fugitive. This officer, disguised as a bushman, travelled quietly to the Bass side of the Western Port. At an appointed place he met a mounted constable, and the two set out Bay. Dressed as swagsmen, and aimed only with concealed revolvers, and Taylor made the seventy-mile journey unsuspected. One day, on the sandy beach, they saw the print of a naked foot, which led to a track in the scrub, and similar footprints at an inlet leading to the water. They conjectured that the hunted man was accustomed to swim across the inlet, and camped in the scrob awaiting his arrival. A man suddenly appears, and is challenged. He vainly runs for the cliff and the river, as the bullets whiz round him. Feeling that certain death awaits him if he does not surrender, Weiberg throws up his hands, and is speedily secured, and brought down to Melbourne. It is believed that the balance of the stolen sovereigns have been secreted by Weiberg in the vicinity of his late haunt, and impressed with that belief, a systematic search has been instituted. Thus far the mystery of the Avoca has been cleared up ; it remains to be seen what further light future events may throw upon it.

Transcript from the The Age 13 Oct 1883 – “The Fate of Martin Wieberg”

Foster. 12th Ootober. The police have identified the boat pickedup on Yanakie beach as belonging to Martin Weiberg. They searched the beach for twentymiles, but found no trace of the body. The captain of the Gazelle steamer, which arrived in Port Albert to-day, reports that be spoke to a craft anchored off one of the Glennies, in charge of Weiberg’s brother, who informed him that his brother Martin had not returned from Waratah Bay yet. It has been since reported that lights were seen on one of the Glennie islands on Sunday night last. It maybe possible that Weiberg is on the island. The captain of the Gazelle intends to pick up the craft on his return, and tow her into Waratah Bay.

Port Albert, 12th October. It is now a certainty that Weiberg has been drowned. He left Waratah in his dingy on Saturday last, the worse for drink. The oilskin coat and other things picked up on the beach are known to have been his. The steamer Gazelle arrived here this morning, and Captain Leith reports having boarded the cutter Ocean, lying at the Glennies, this morning, and found Weiberg’s brother alone, in charge, anxiously waiting for Weiberg’s return..Leith describes the cutter as a smart little craft of about 10 tons.

Transcript from the Bendigo Advertiser 16 Oct 1883 – “The fate of Martin Weiberg”

In order to solve the doubts as to the death of Martin Weiberg, the notorious gold robber, a World reporter was commissioned yesterday morning to interview Captain Leith, of the schooner Gazelle. Captain Leith stated that there was a fierce wind blowing from the north-east at the time, the sea was mountains high, and it was impossible that Weiberg’s dingy could live long in such a gale.

“Do you think that Weiberg had any idea of committing suicide ?” said our reporter.

“Not the slightest,” replied the captain, “he was far too clever a man for that. He had been drinking hard, and was half drunk at the time, and his death was simply the result of a reckless drunken spree.”

“What about the gold ?” was our reporter’s next question.

“Of that I know nothing at all, and I don’t believe any living person does either.”

“You are quite sure he is dead anyhow ?”

“I am perfectly sure that he is dead,” replied the skipper, “and I offered to bet a friend of mine.”

About a year subsequently the Detective department of this city received information from a private source that Martin Weiberg, who had been the ship’s carpenter on board the China at the time of the robbery, but who was then a selector on the Tarwin River in Gippsland, was the robber. A party of detectives where sent out to capture Weiberg, whom they met as he was on his way into the city. He returned with them to the place where he had been living, and a search revealed a number of ” wreath” sovereigns hidden in an old plane by means of a hole bored in the wood. Weiberg then declared that he had only been a tool in the hands of Captain Ellison, and was now ready to show them where the remainder of his portion of the gold was hidden. He said he had placed it in an old iron kettle, and sunk it in the Tarwin River. The detectives went to the place under Wieberg’s guidance, and while they were fishing for the precious pot with a boat-hook and line, he managed to effect his escape. Soon after this the detectives found 1,000 of the sovereigns at Emerald Hill, where, it was pretty certain, they had been left by the clever rogue.

After several months hiding in Gippsland, Weiberg was again captured, tried, and sentenced to five years in Pentridge. The next day after his release from that institution, about three months ago, he was charged at the Hotham Police Court with having been drunk, and was fined £1, including costs. He paid the fine with a ” wreath” sovereign, and went away to Gippsland, where subsequently he spent a lot more ” wreath ” sovereigns at a public-house. In this connection it should be mentioned that immediately upon the discovery of the robbery and receipt of the news in Sydney, the coining of wreath sovereigns was discontinued, and only the one box of them ever found their way or were allowed to get into circulation. The device on the colonial sovereign was then changed to St. George and the Dragon, so that the fact of Weiberg’s having so many of the old pattern to dispose of, even after his long incarceration in Pentridge, has a peculiar significance. Less than one-fourth of the stolen money was ever recovered.

The Launcheston Examiner 20 Oct 1883 – Interview of Capt John Leith